Datuk Seri Nazri Aziz, the minister in charge of law affairs, said the matter had not been raised at the Cabinet level.

“It (judicial caning) remains for now. If it needs to be reviewed, it will be discussed in Cabinet, but it has not been brought up. We’ll just wait and see,” he told The Malay Mail.

The Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department was responding to a call made by human rights group Amnesty International urging Malaysia to abolish the punishment.

Amnesty’s Asia-Pacific programme researcher Lance Latigg had told a Press conference here the practice was a “severe violation of human rights”.

The London-based group, in its recently released book A Blow to Humanity: Torture by Judicial Caning in Malaysia, claimed up to 10,000 prisoners in Malaysia were caned every year, with 6,000 being illegal immigrants from neighbouring countries.The group also urged neighbouring countries such as Indonesia to pressure Malaysia into abolishing judicial caning.

Nazri, however, said Amnesty could lobby for other countries to pressure Malaysia.

“Latigg spoke to me. He said he would raise this issue with Indonesia and other countries. That is not a problem. They have every right to do so. However, only we have the right to make decisions in this country. Other people cannot dictate that to us.”

Malaysia attracted international attention after Kartika Sari Dewi Shukarno, a Muslim woman, was sentenced to six strokes of the rotan and a fine last year for consuming alcohol in public. The case received hostile response, especially from human rights groups and women’s rights activists. Kartika’s sentence was eventually reduced to community service.

Singapore too attracted widespread condemnation in 1994 when American teenager Michael Fay, then 18, was sentenced to six lashes upon pleading guilty to vandalism after confessing to spray-painting and tossing eggs at several vehicles.

Spare the whip, say NGOs

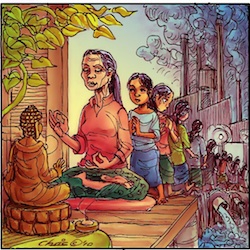

KUALA LUMPUR: Human rights activists want the government to abolish caning as a form of punishment.

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) told The Malay Mail they were opposed to de facto law minister Datuk Seri Nazri Aziz's stand on continuing with caning sentences.

Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (Suhakam) commissioner Muhammad Sha'ani Abdullah said: "Malaysia, as a member of the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council, is expected to ratify and comply with international human rights conventions, so the argument that Malaysia adopts 'progressive realisation' is not a reasonable defence to delay ratification of conventions against torture.

"There is no advantage for Malaysia in avoiding the ratification, and it is also in line with the government's 'People First, Performance Now' promise."

Tenaganita director Irene Fernandez, whose organisation promotes the rights of women, migrants and refugees, said: "We have said for a long time that caning is wrong. Caning has become a tool of torture. We believe offences under the Immigration Act is not crime as offenders usually had no proper documents or overstayed. Caning of such offenders is not just unfair, it is torture.

"Back when the law against human trafficking was enacted, there was no whipping punishment for traffickers. At the time, Nazri himself said there was no whipping because according to the UN, it is wrong. So, caning as a form of punishment should be abolished."

Suara Rakyat Malaysia (Suaram) chairman K. Arumugam said: "We support Amnesty International's call for Malaysia to abolish caning. Suaram is against capital and corporal punishment as it is contrary to our constitutional guarantee of the right to life."